3rd Arm Inc

Pioneering a new category of articulated wearable devices

Duration

3 years

Team

Dr. Kenneth Salisbury, Austin Epps, Shenli Yuan, Alberto Bambach, Jaeyong Sung

Role

Research Assistant (RA), “Passive Arm” Sub-Team Lead, Cofounder

Overview

I worked for 18 months as a research assistant in the Stanford AI lab on a project to explore and develop smart wearable “3rd arm” robotic devices. Over the course of the research phase I was able to serve an instrumental role by fusing design thinking with the technical research approach.

My early prototyping efforts around simpler devices yielded such promising results that the PI (Dr. Kenneth Salisbury) decided to form a separate division of the project to explore non-motorized devices, which I led. This eventually became the central focus of the project. I was retained as a consultant after I graduated and am now leading the effort to continue developing the technology and commercial applications with Dr. Salisbury in our spin-out company: “3rd Arm Inc”.

Over this process, we have filed four patents, raised offers for pre-seed funding, presented research findings for SAIL-Toyota, and exhibited in Dubai.

I have divided this entry into four sections:

Early work and prototyping

Research and engineering

Testing

Commercialization push

Early work: prototyping and leading design process

The original “duct tape” 3rd arm prototype

In my first few weeks on the project I created a series of influential prototypes, starting with one that only took 10 seconds to make.

The complexity of such an ambitious project meant laying the groundwork was no mean feat. Soon after starting, the project was becoming mired in debates around myriad technical considerations: kinematic layout, number of degrees of freedom, control scheme, motor power, how to incorporate machine learning, and so on.

To help “unstick” the team from analytical approaches that were generating more questions than answers, during one meeting I taped a rod to my waist and started pantomiming different kinematic arrangements. The attention of the room shifted to the prototype and the team started zeroing in on insights about the most viable layouts and their implications for the other questions we were grappling with. This moment made an impact on the team, and I stepped into a design leadership role.

Over the rest of the project I was able to redirect the group culture from primarily discussing roadblocks at meetings to being more proactive and bringing prototypes to share. This clarified which issues actually needed group input, energized the team, and helped make their ideas more tangible.

One way I shaped the team design approach was to demonstrate being “mindful of process” - to consider which approach or toolkit a problem calls for, instead of instinctively reaching for the hammer of engineering. One form this took was coaching “pretotyping” or “physical sketches” to explore a design before committing to more expensive and detailed prototypes.

Another theme I frequently coached was to separate consideration of potential solutions from technology and implementation. For our talented team of engineers, technology approaches were almost synonymous with innovative solutions, so they found it foreign to consider potential solutions without immediately jumping to discussion of technology.

In one meeting, we were discussing adding actuated joints to an arm to allow it to automatically “gimbal” and track a target with a flashlight. Some of the team immediately started making preparations to produce this functionality, which would have taken several weeks to complete. Instead, I guided the group in testing this idea more quickly. We used an existing unpowered gimbal to hold a flashlight, attached a thread to its front and to a chair, and were able to actually evaluate the usefulness of the tracking functionality before the meeting ended.

Research and engineering

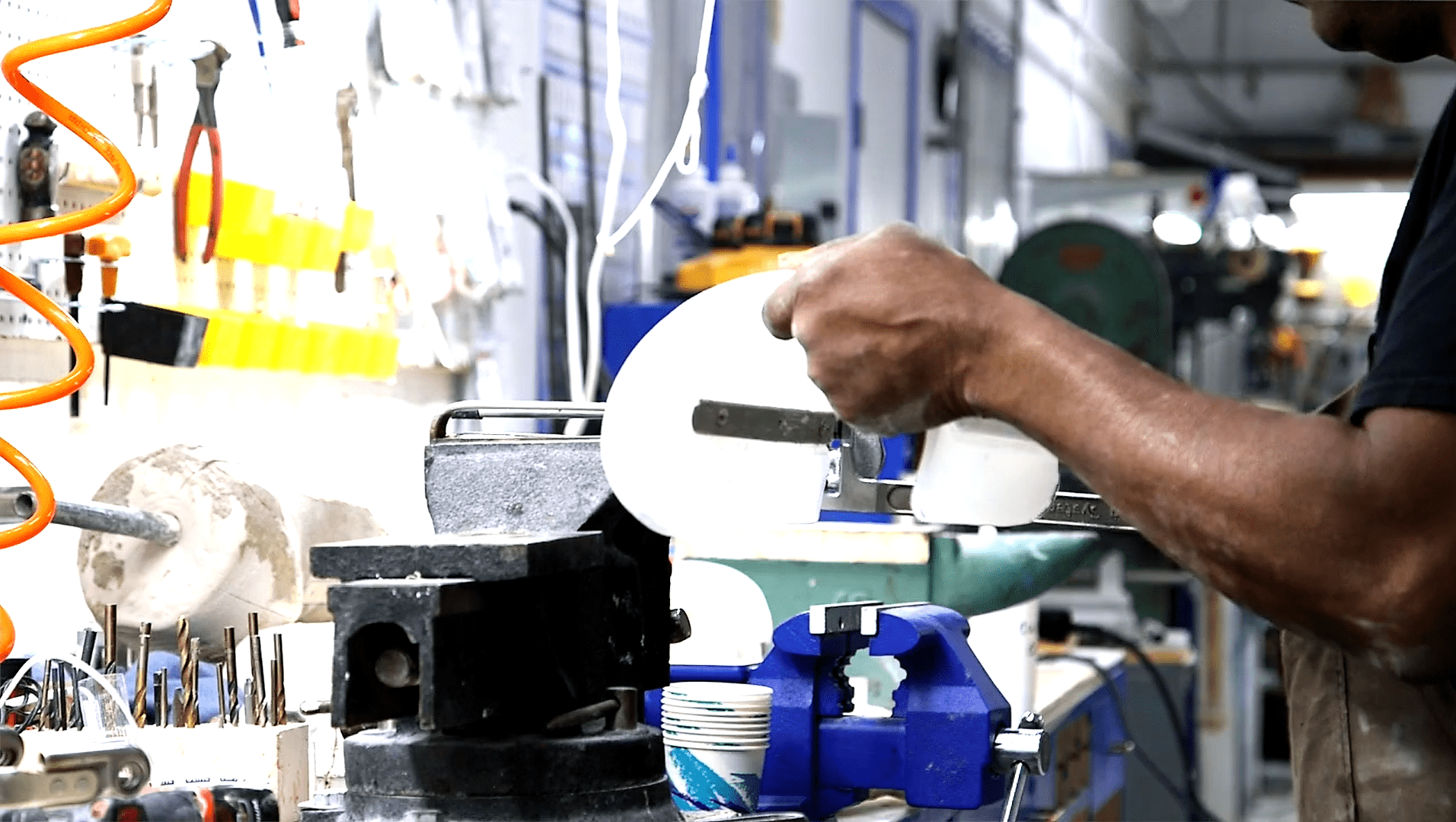

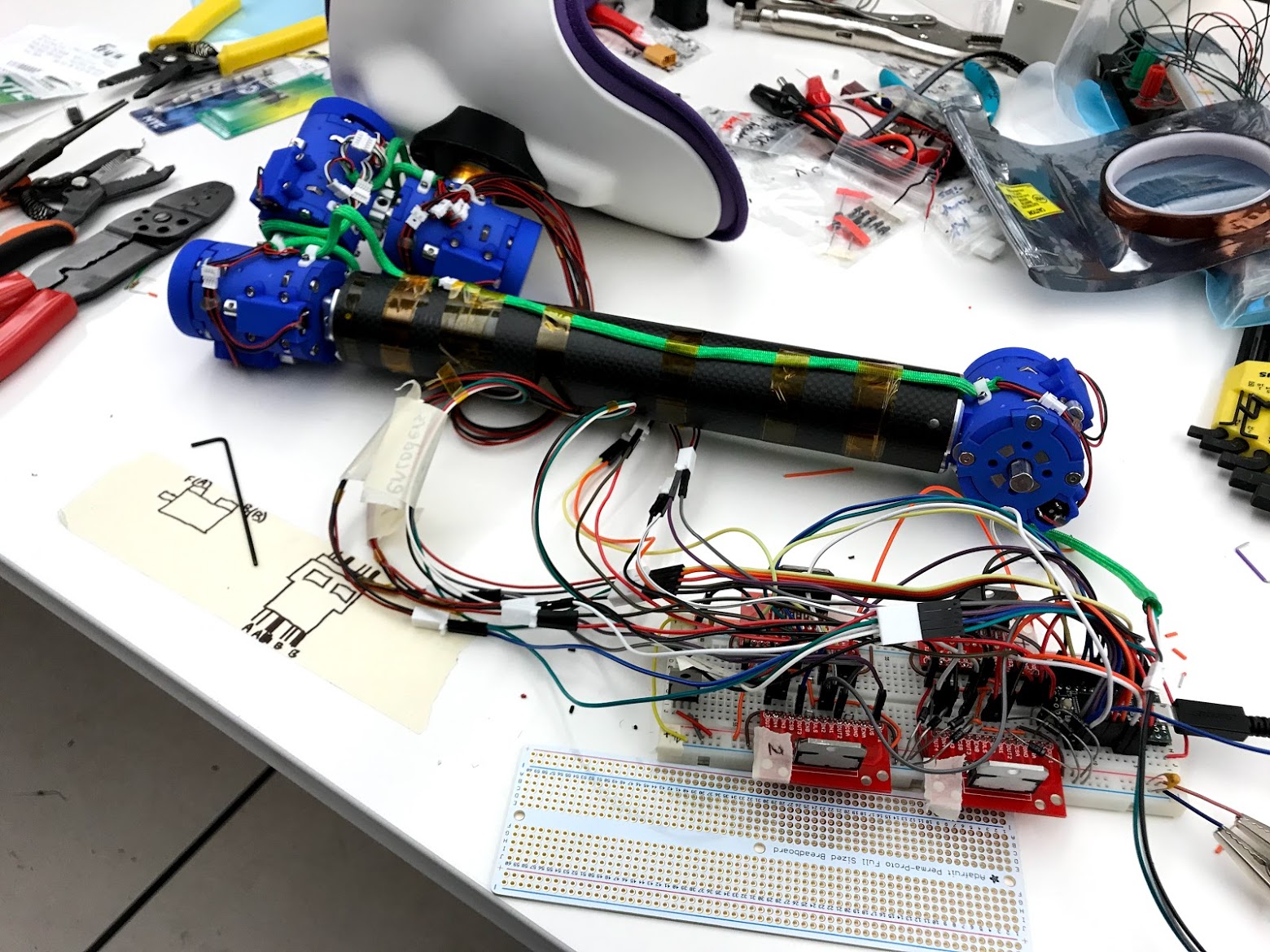

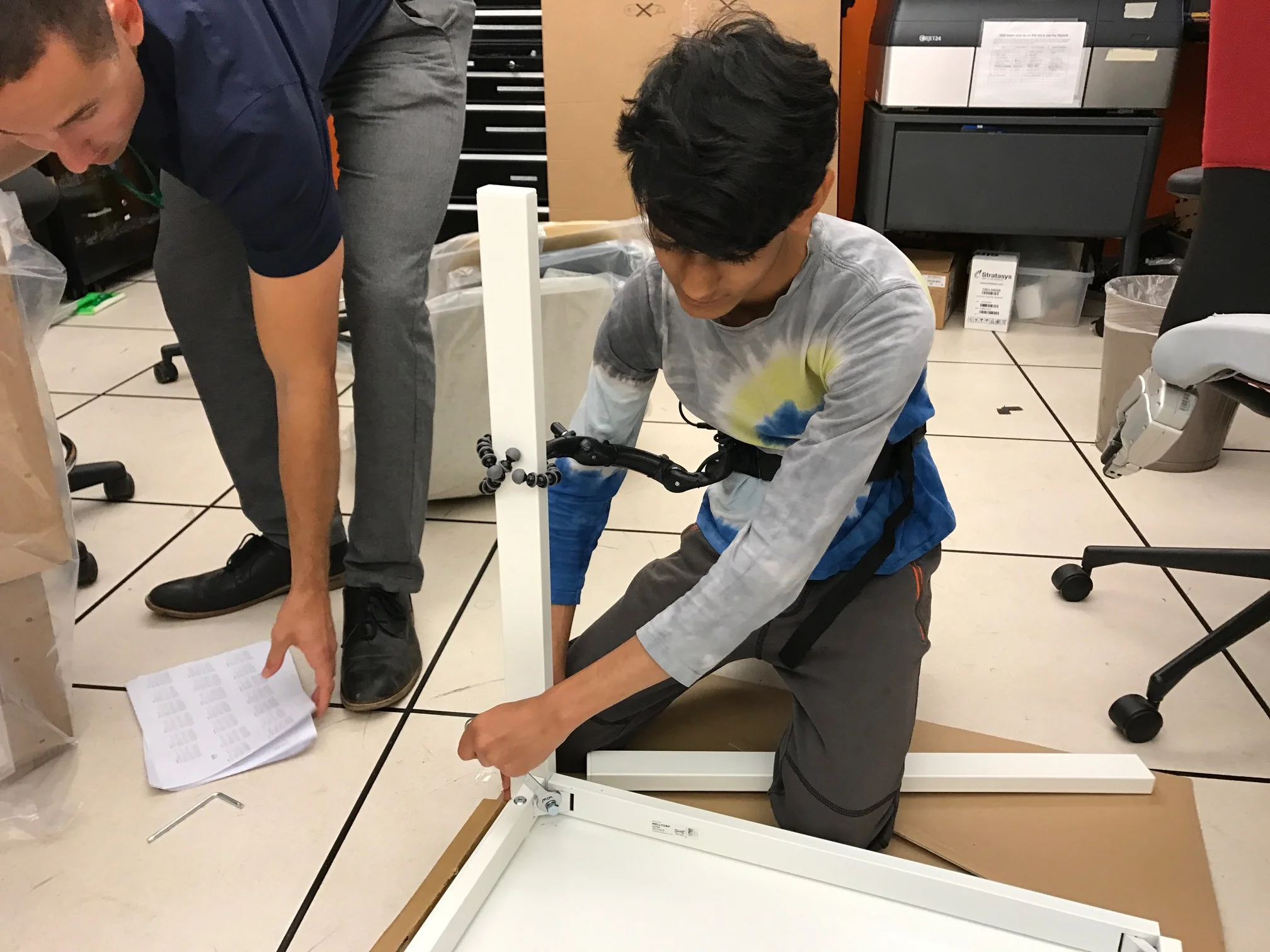

I also did the role of an engineer on this project and made a number of refined prototypes.

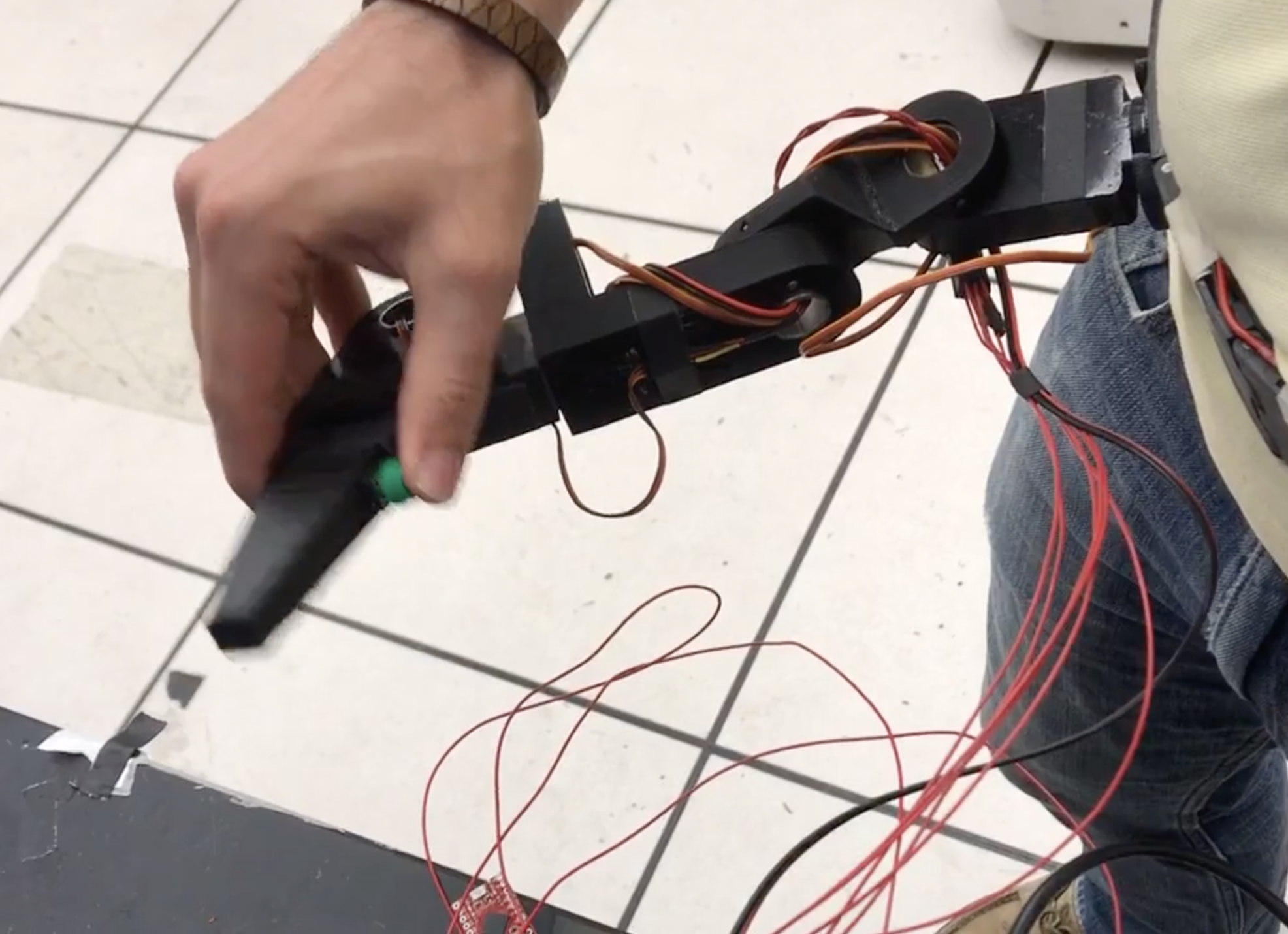

I worked with Bill Verplank (one of the pioneers of interaction design) on refining our strategies for interaction and to design hardware with good affordances, signifiers, mapping, etc. to make our prototypes intuitive for novice users.

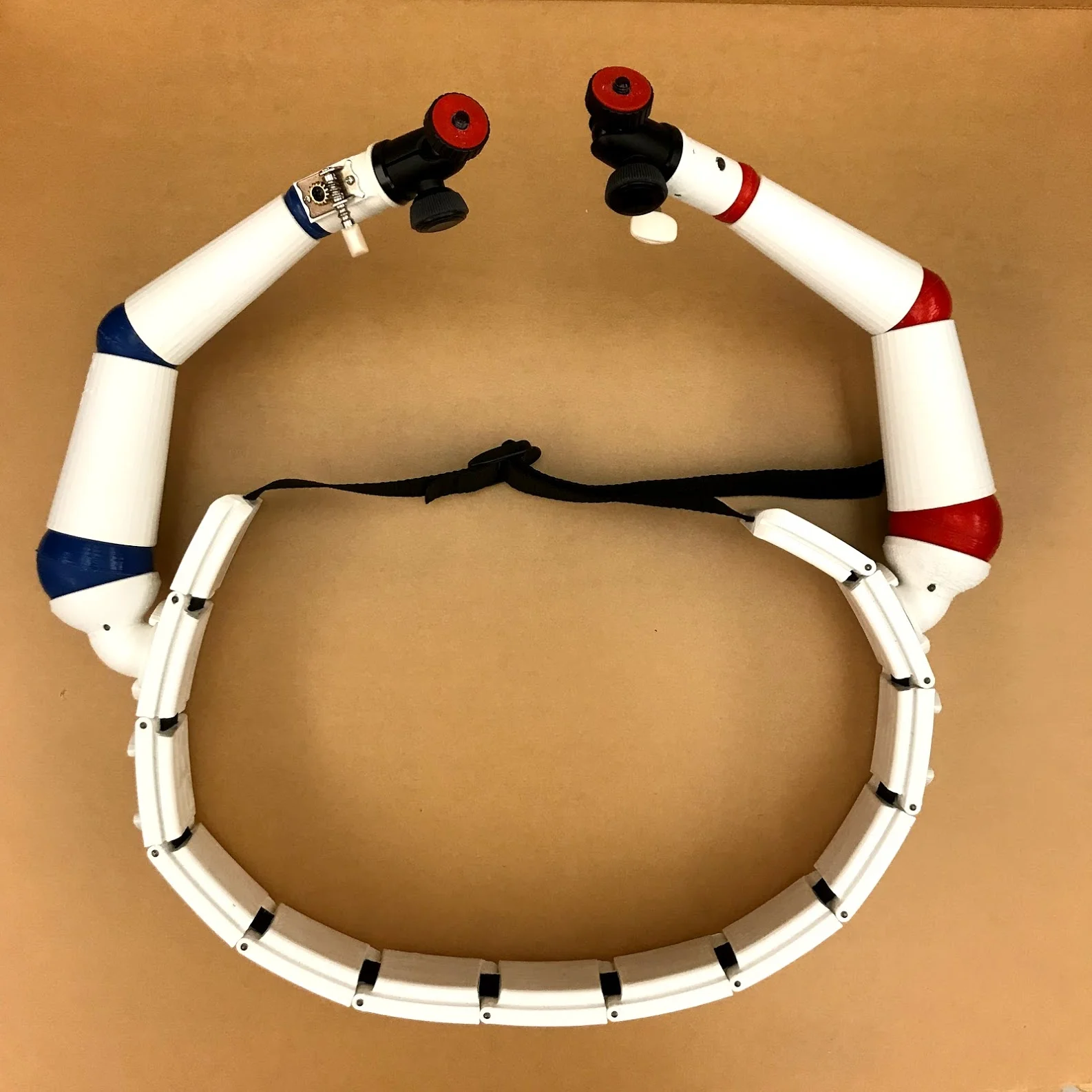

Comfortably mounting mechanical hardware on the body for extended periods of time is a tricky design problem. I worked through many approaches to body mounting and one of my favorites is a design similar to a linked watchband worn as a belt, which is deceptively simple. Hips can comfortably support lots of weight and the pelvic bones offer a remarkably stable mounting surface. The belt is rigid in axes all but the vertical axis, so it easily conforms to a user’s hips while its rigidity in other directions means that force and torsion resulting from an attached arm is spread evenly over the wearer’s waist. It also utilizes a Fidlock magnetic buckle which allows it to be donned and doffed (taken on and off) in one step. Because prosthetic devices are the closest body mounting analogy, I worked with a prosthetist to refine the designs.

Another significant effort we undertook was to design a new kind of electromechanical brake that would allow the arm to seek and lock in a desired position without actuated joints. This was accomplished by joints with electrically selectable ratchet direction that could travel in either direction with less than a degree of backlash. (patents pending)

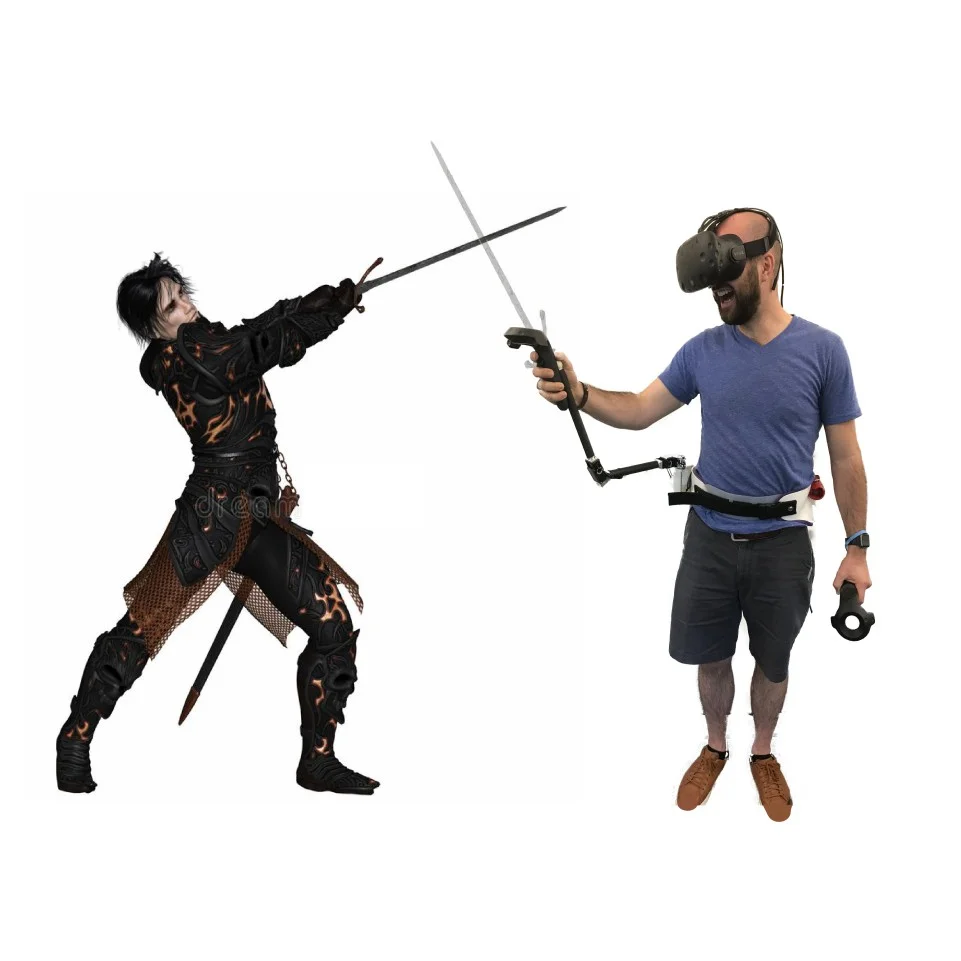

In another branch of the project, we designed fully robotic prototypes that could do various tasks under voice control as well as function as a kind of wearable joystick control interface with haptic feedback. We also used these devices for haptic feedback in virtual reality, which gave promising results. This means that a small wearable can provide true room-scale force feedback for a user’s arms, which could enable a much greater degree of realism than current haptic feedback based on vibration. (patents pending)

I have included a selection of unpowered prototype designs below and some of what we learned from them (scrolling gallery):

A poster that I exhibited at a Toyota-SAIL conference. One prototype that I exhibited at Dubai Design Week’s “Meet The Future of Design” showcase was worn by the Sheik of Dubai!

Testing

I pushed the team to test of our prototypes early and often which produced valuable insights for designing subsequent iterations.

Aesthetics: Our first tests outside the group revealed that the initial prototypes were too ugly for even Pokemon Go users to be willing to wear! This confirmed that there was some aesthetic and cultural risk (since we were perhaps even stranger than Google glass!) and suggested industrial applications might be more accepting in this respect. We made sure subsequent designs were more and approachable.

Durability: Another early prototype broke within five minutes of handing it to a tester, which clarified what loads novice users expected the device to support.

Sizing: An early industrial test in a Toyota manufacturing plant revealed that design was too bulky and the automotive assembly environment too risk-averse to be a good first market for this kind of technology.

Interaction: Many tests underscored the importance of being intuitive to use, easy to put on and remove, and stow on the body when not needed.

Insights from our prototyping and testing efforts led to us producing a passive device with a simple and nonthreatening form, reasonable strength, extreme robustness, “fail safe and soft” rubber joint design, and extremely fast and easy interaction paradigm: flipping the red lever up to unlock and down to lock.

Taking the refined passive arm for a stroll

commercialization push

This refined design received a strong response that suggested it has commercial potential, so for the last phase of the research funding we began investigating potential applications for passive 3rd arm designs.

Our vision is based around the premise that people have limited physical capability. Humans have only two hands, limited dexterity and speed, are easy to fatigue, etc. As a result, there are lots of startups working to automate various kinds of tasks, although it’s becoming clear that completely automating physical tasks which take place in unstructured environments is difficult because sensing and AI can’t yet handle much unpredictability.

We believe that for many kinds of tasks, human augmentation will be the best approach. By leveraging what both humans and machines do well, this will allow fewer workers to accomplish more in totally new and better ways.

Preliminary testing at Amazon fulfillment centers suggests that our devices could be valuable for stowing (putting items into inventory) and picking (pulling from inventory to fulfill an order) by holding the worker’s scanner and freeing up both their hands to manipulate packages. The un-augmented Amazon worker on the left takes significantly longer to stow (due to being encumbered by holding the scanner) and experiences greater frustration, which contributes to attrition.

Our observations and testing have revealed that there are many naturally “3 handed” physical tasks for which one hand doesn’t need to take an active role. Our preliminary tests show that in these cases, a passive body-referenced third hand can significantly enhance productivity. This suggests promise for lower-tech devices, which could be launched quickly and then imbued with greater performance and sophistication as individual use cases dictate. Eventually we plan to leverage upcoming technology improvements to provide workers with greater precision and speed for certain tasks, such as enabling an untrained worker to weld with superhuman skill.

A selection of tasks we are evaluating for commercial potential:

Selected field tests: