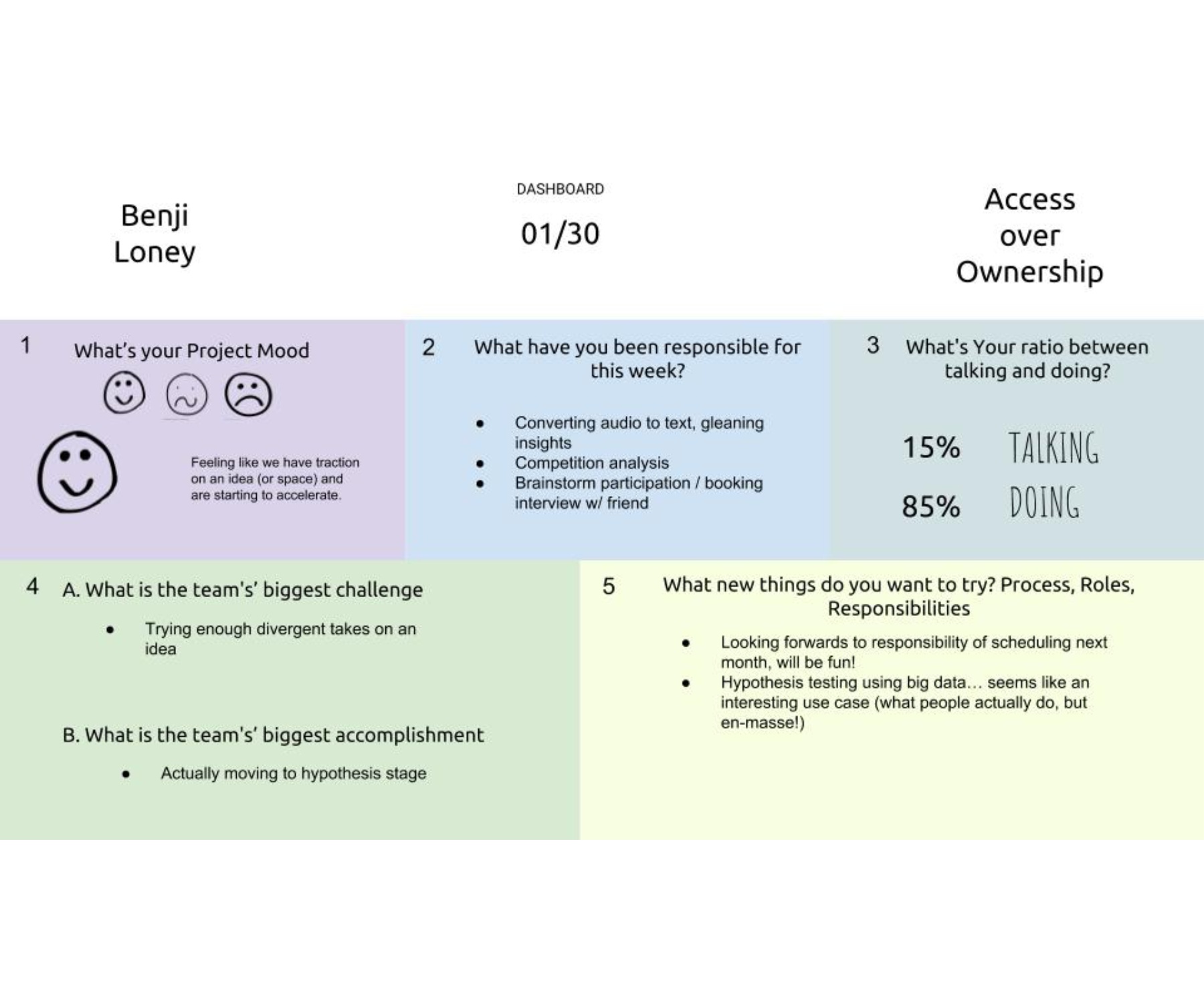

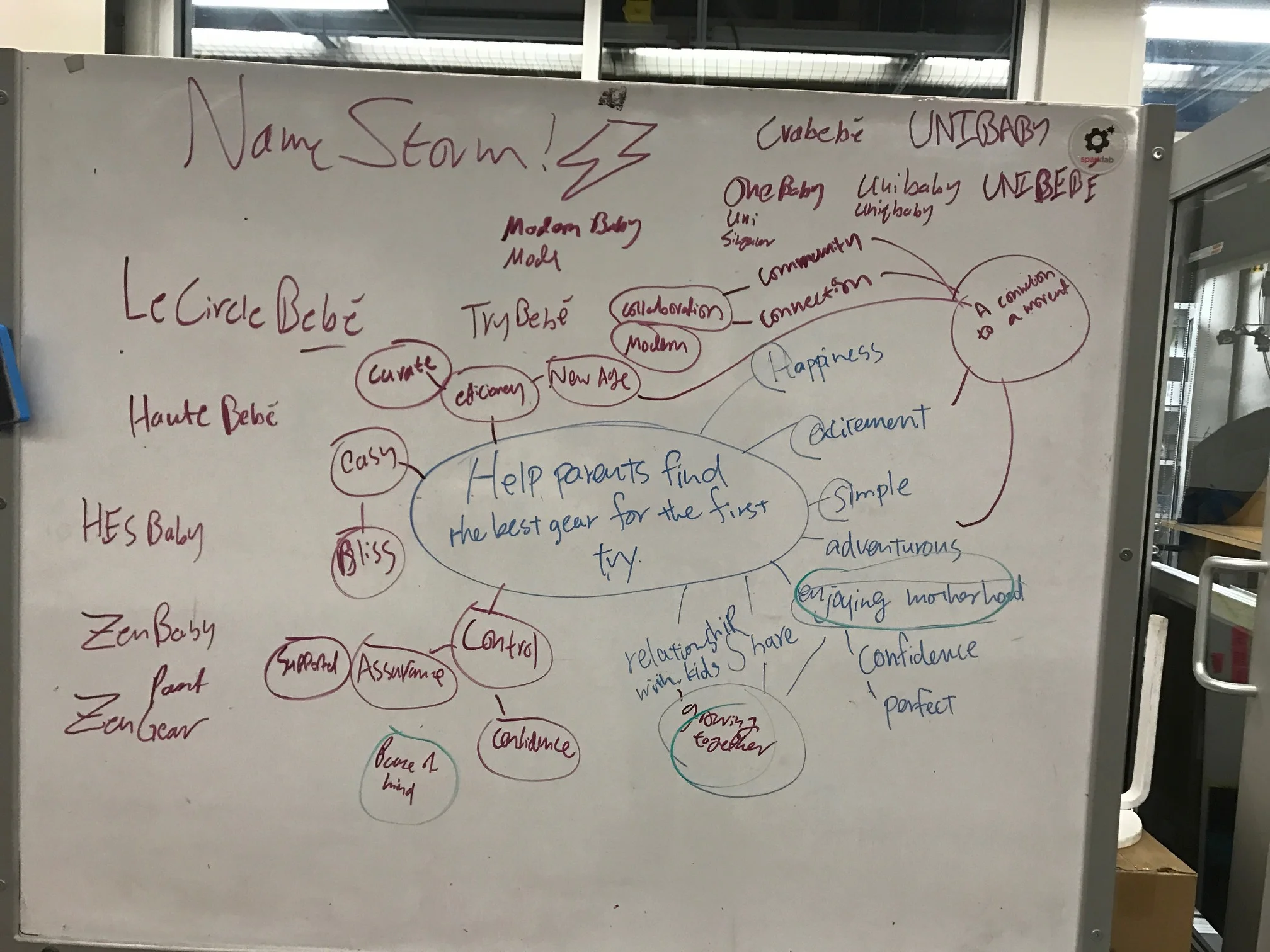

UNIbébé

Reimagining the new parent product experience for the millennial generation

Brief

Significant recent changes to how professionals plan and structure their families mean that traditional retail models for acquiring baby gear don’t work well anymore.

Using human-centered design methods, I discovered this area of cultural change and led a team on a 6 month design project at Stanford to address these challenges during my Schmidt MacArthur Circular Economy fellowship.

Today's professional parents now have fewer children in their 30's after becoming professionally established while living in cities away from family and trusted networks. They have the inclination to buy whatever will make their life easier, although are often bewildered by sheer volume and variety of modern gear options. Less storage space in city dwellings and smaller families for hand-me-downs also means they desire to discard gear as soon as it is outgrown. (see footnote)

This means the traditional model of large families started in couples' early 20's (and thus being cash-strapped and inclined to DIY or do without), entrenched in long-term trusted communities with efficient means for exchanging used products no longer holds for a large segment of the population.

As a result, traditional retail models for baby gear often don’t meet millennial professional parent's needs.

Participatory observation: immersing ourselves in the experience of expecting parents (and learning proper swaddling technique) at a childbirth education class

Additionally, the status quo of short product usage windows with inefficient reuse and rapid devaluation of baby gear is very wasteful (resources + embodied energy), so we were also inspired by concepts like Circular Economy to seek a solution which would be better for parents while conserving resources for their children’s generation.

We believe that a systemic change in how baby gear is accessed is the most powerful leverage point for broader sustainable change from a systems thinking perspective. For example, an access instead of purchase model which produces profit not from unit turnover in a factory but hours of service in the field could produce significant structural shifts in industry with positive environmental impact. This re-alignment of incentives could result in brands designing and manufacturing products for higher quality and durability with less wasteful fashion cycles and better infrastructure for reclaiming and remanufacturing of products.

A virtually new motorized baby swing. Although this is a highly-rated $250 product, it was handed off to Goodwill to free up space because it was only effective for a few weeks.

Key Insights from Ethnographic interviews

Parents are frequently more desperate to get rid of gear than they are to acquire it.: “Don’t get stuck (with used gear you don’t want)”

Families we interviewed simply couldn’t throw things away; things had to go to another family which can be challenging to find. Many parents had stories of unwanted gear being dumped on them. The constant inflow of new products for each development stage means parents are always fighting back the clutter.

Gear doesn't generally get worn out:

Short usage windows: “It's an expensive piece of technology in almost brand new condition” “You use it for like a month or two, and then you just have this thing in storage (laughs)”

Nice gear is often still pristine when passed along due to extremely short usage windows or unanticipated unsuitability for a given family or baby.

Contamination and safety fears create market failure: “What if a diaper leaked on it…”

New parents have a powerful fear of germs and contamination for their first baby, which results in a market failure for used products, especially when parents don’t live close to family or other trusted networks for acquiring and passing along used gear. This fear applies to just about anything. There are also safety worries related to used product integrity: none of the families we interviewed would ever consider a used car seat except perhaps MAYBE one acquired from immediate family.

Environmental consequence: broken networks of trust often mean that gear loses desirability disproportionate to utility and gets rapidly cycled down the socioeconomic scale to the landfill, instead of being passed around between peers until it wears out.

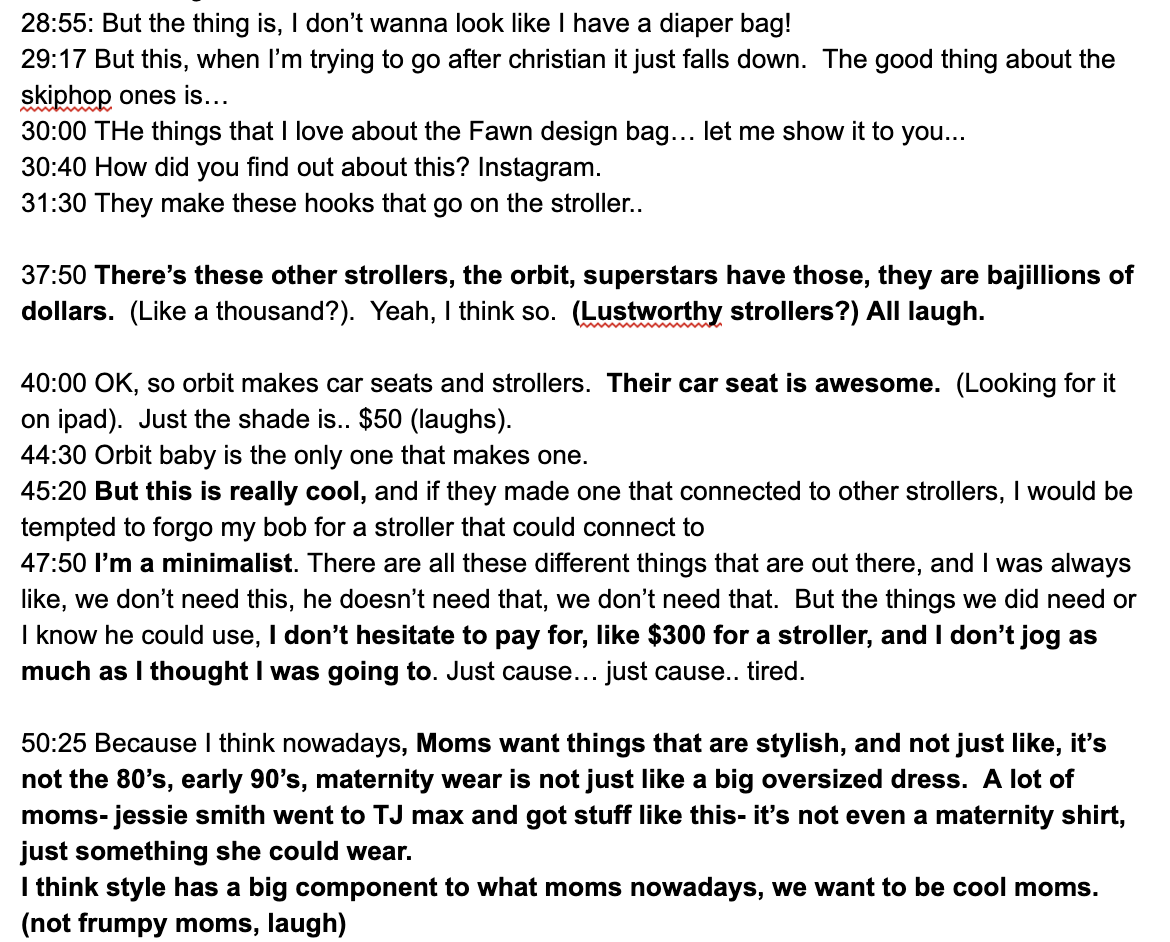

Identity transition can be hard: "I want to be a cool mom, not a frumpy mom"

For women with professional careers, managing identity during the transition to motherhood can be challenging. We found moms who strive for “it” brand gear and follow chic mom instagram accounts with picture-perfect photos.

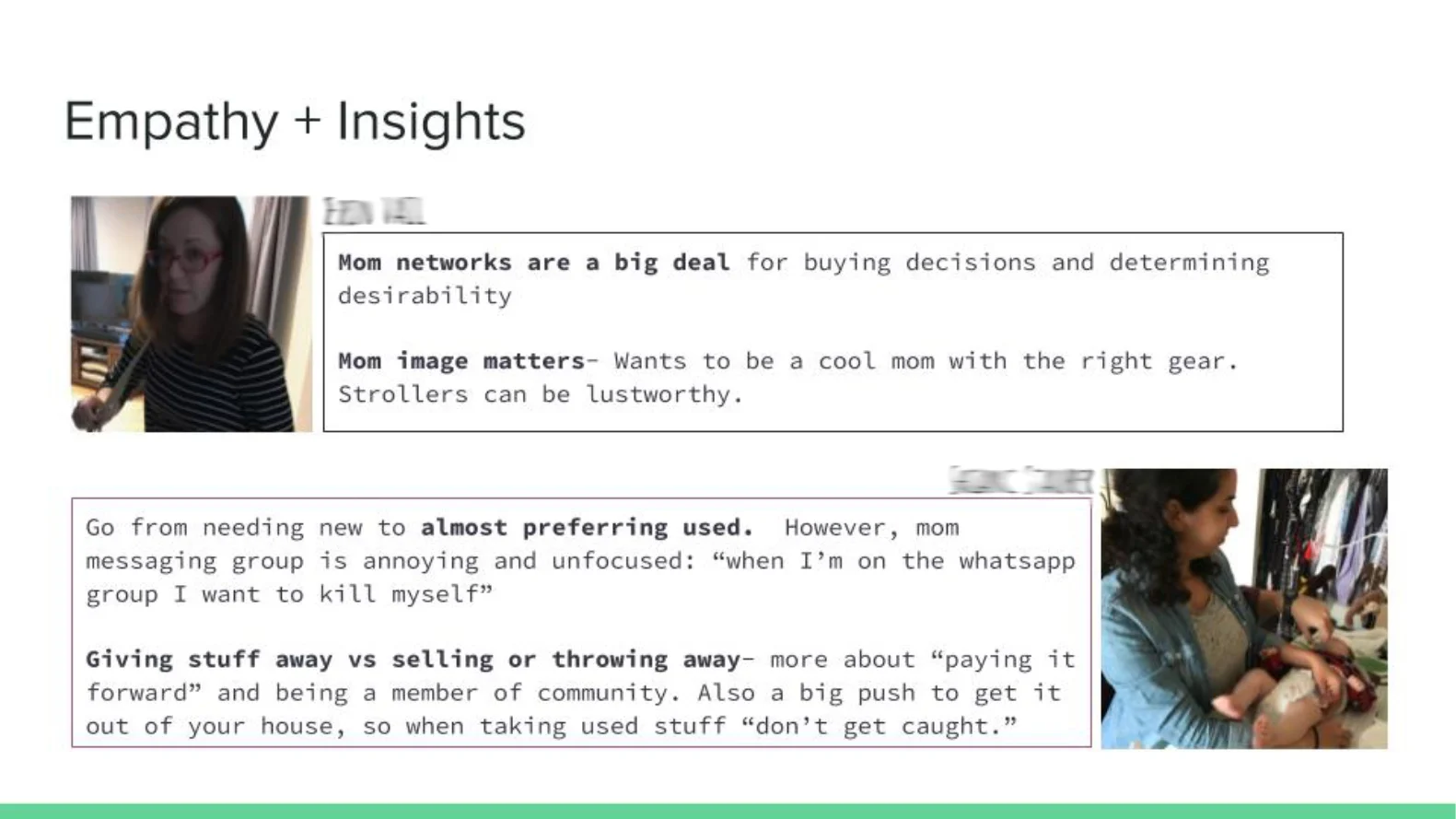

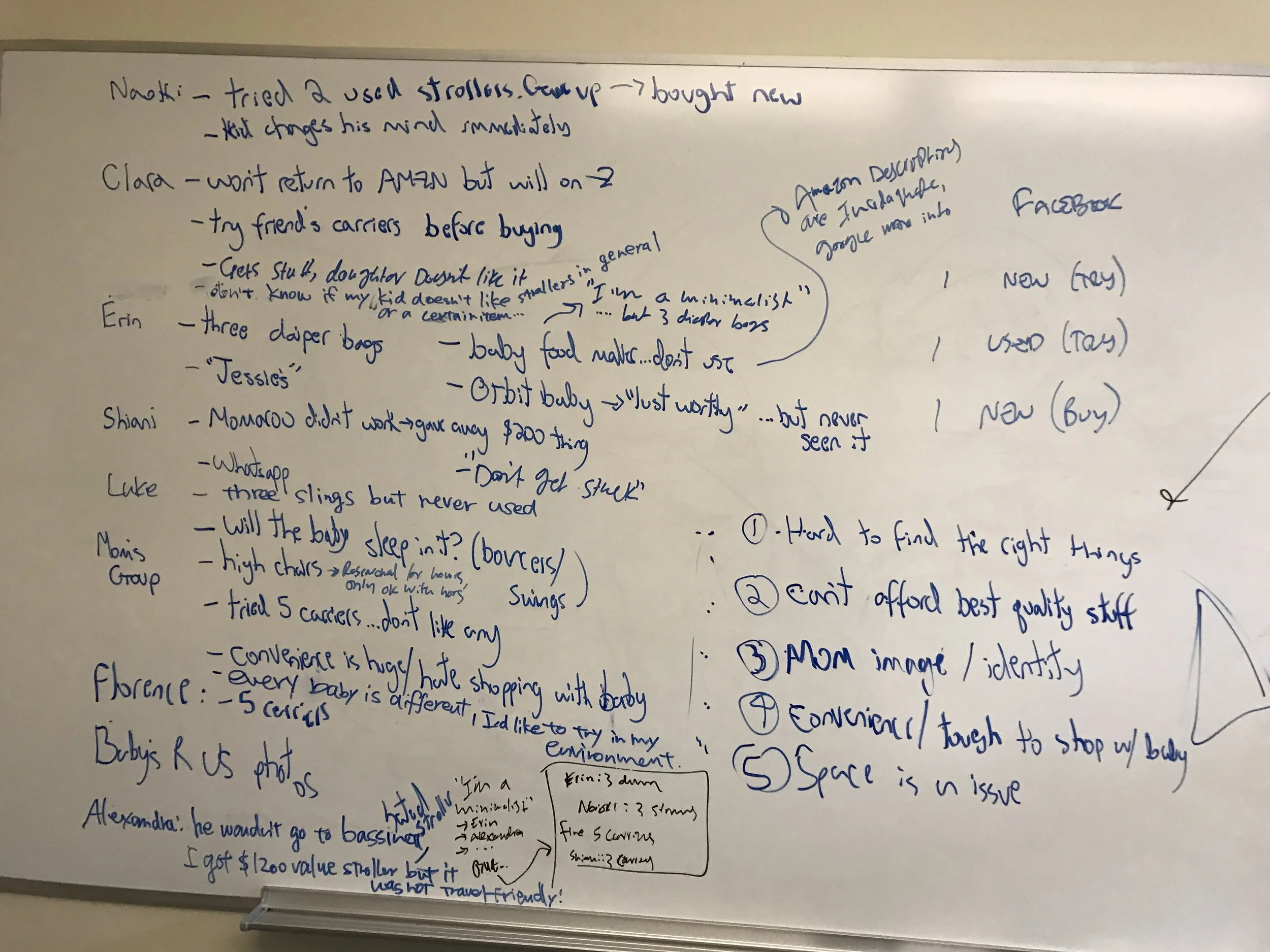

Raw transcription notes from parent interview

Notes were condensed into slides for presentation on the “empathy” phase of project

Initial prototyping efforts:

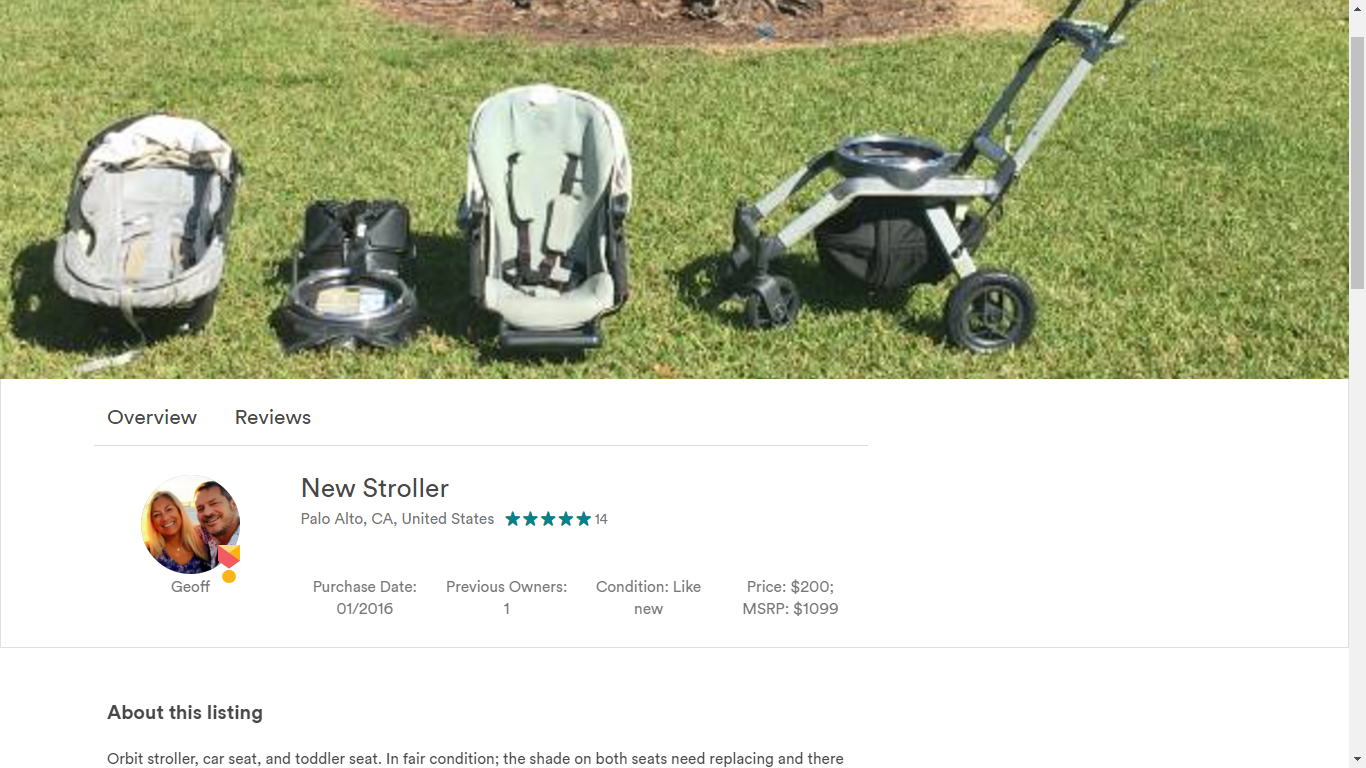

We initially prototyped around facilitating family-to-family gear swapping. We assumed that providing better information and pictures upfront would fix the problem of used gear being forced on a parent, and that generally increasing trust between families through review systems similar to Airbnb’s was the key to fixing the market failure for used gear.

However, one mom who had raved about the “Orbit Baby” stroller wasn’t actually willing to commit to buying it used at a steep discount, not because she didn’t trust the couple selling it, but because it turned out that she had never seen one in person! This revealed that firsthand experience with unfamiliar products was a more fundamental issue than trust between families.

A lightweight prototype we used to assess willingness to buy gear from other parents. Done in 10 minutes using Google Chrome “inspect element” functionality to inject different photos and HTML into an existing Airbnb page.

Subsequent interviews revealed additional insights with similar themes:

Finding the right product is hard: "One of the things you find out when you have a kid is there's no such thing as average”.

Myriad new product introductions and varieties of each mean that every need has multiple possible solutions, but wading through it all and evaluating what to get and what to pass on is really tough. While attending support groups, we learned that parents tend to lean on reviews and recommendations from friends, but this often fails due to lifestyle or individual baby differences.

Existing ways of trying out gear aren’t realistic: “I've probably got 5 or 6 different (baby carriers) at home because I just don't know, I think this one’s going to work, but nope my back hurts, or he doesn't like it.”

Trying a product in the store for few seconds doesn’t tell parents if it will work for their changing lifestyle or baby. Parents often pass on entire product categories and just get by without due to shopping fatigue. Although Amazon allows free returns, parents don’t return gear that isn’t working out because it "feels wrong." The issue of how frequently parents regret their gear buying decisions also came up in interviews with a Doula (birth coach) and while taking a childbirth education class.

This led us to reconsider our approach and formulate a new new point of view (POV):

It would be game changing if… parents could try products out IN THEIR OWN ENVIRONMENT before they bought them

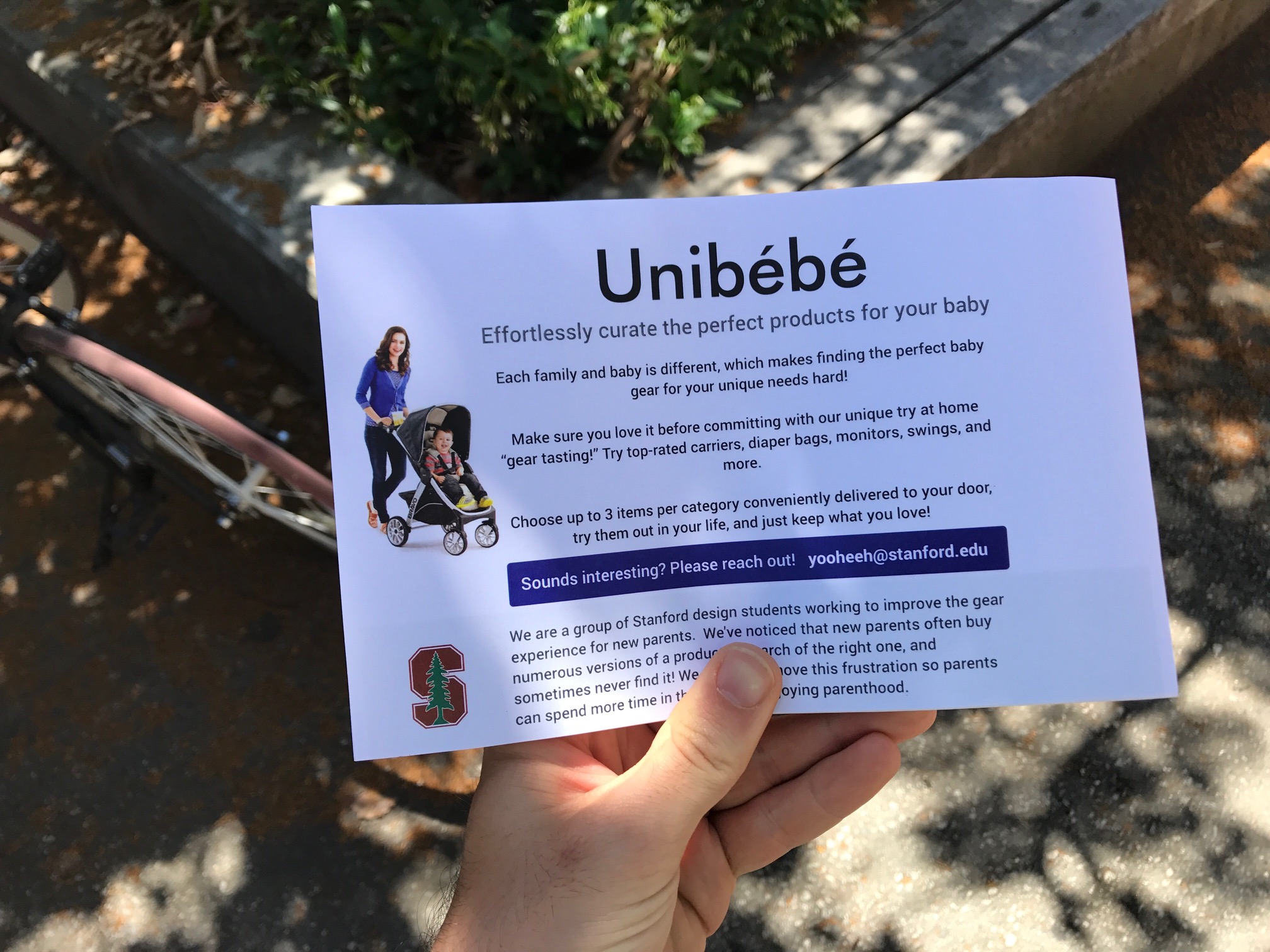

Prototype: UNIbébé Gear Tasting

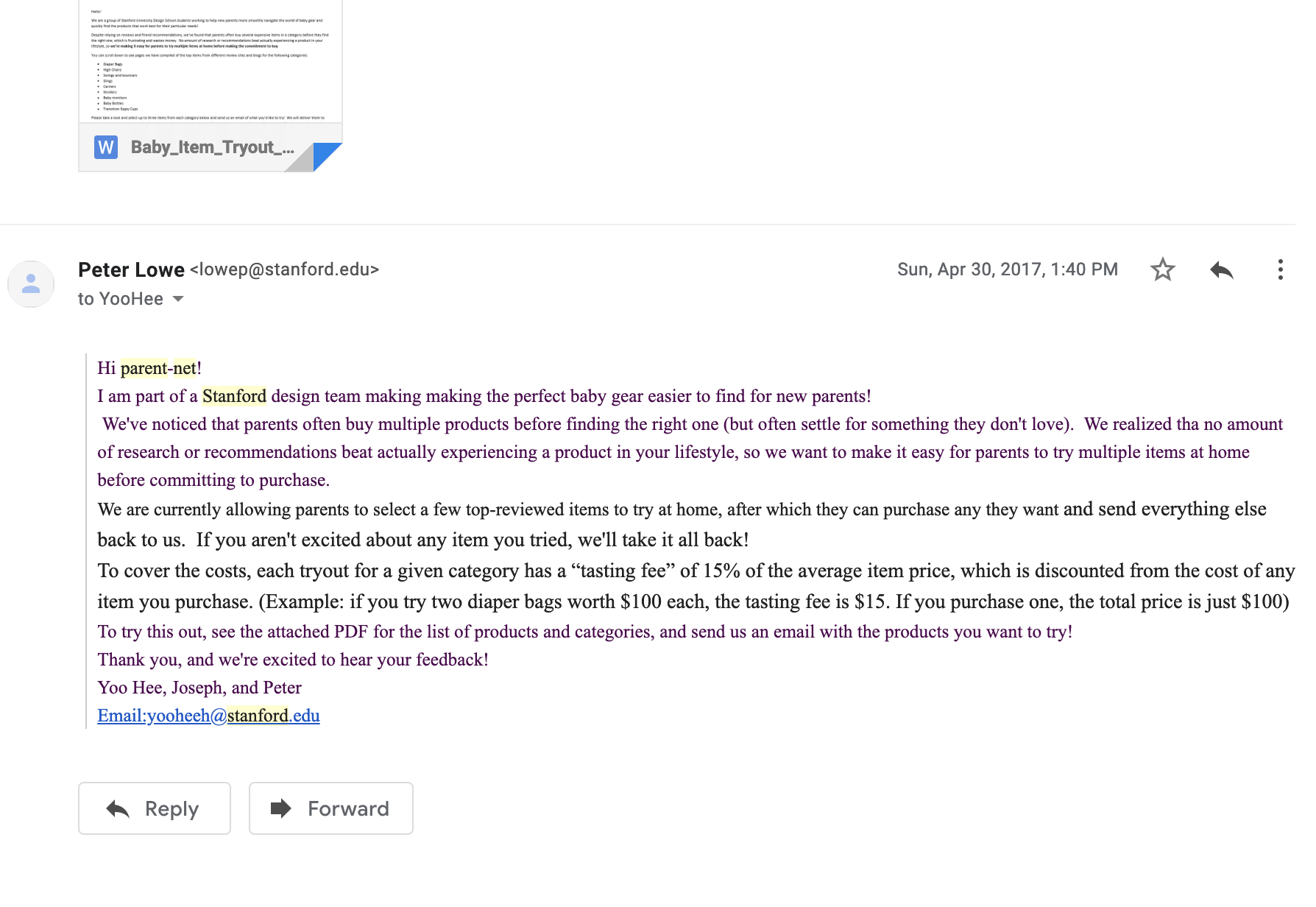

Working off the new POV, we prototyped a service to allow parents to try up to 3 comparable pieces of gear at home for two weeks in their actual lifestyle before committing, for a small "tasting fee” to cover shipping and handling of products (which was partly refunded if a family purchased items).

A video we created to educate customers about our gear tasting prototype

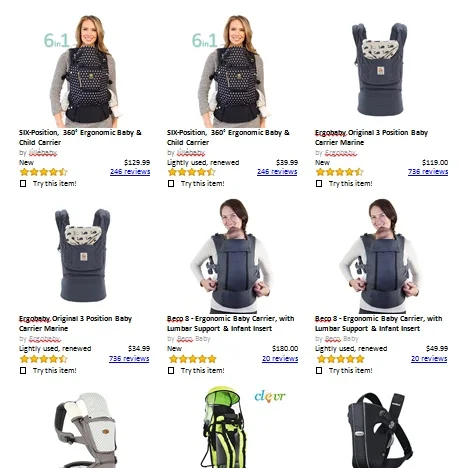

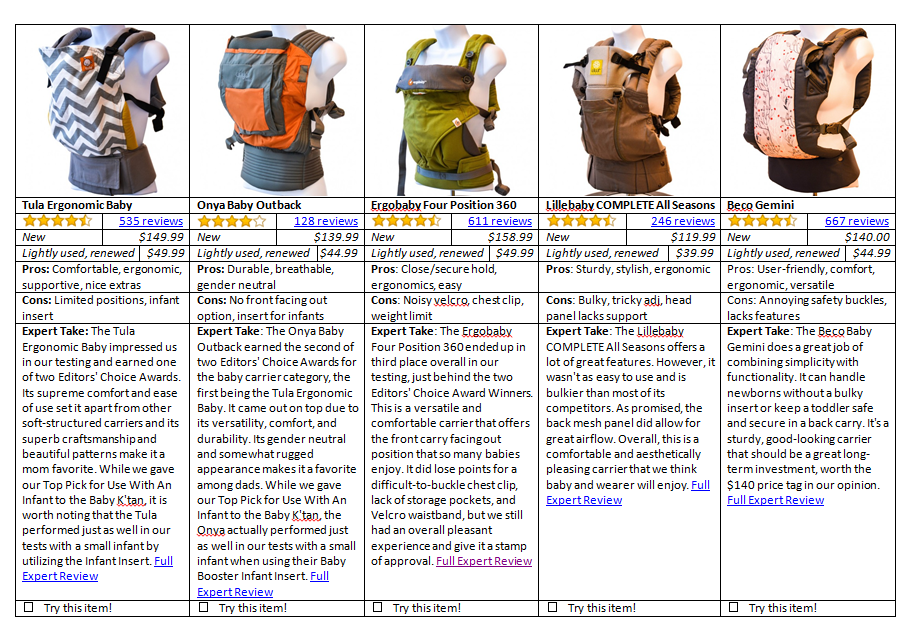

Parents could access a curated selection of the 5 top-rated pieces of gear in each category, and when a family requested to try some products, we would give them not-yet purchased gear from our current circulation or purchase the items on Amazon, and return items that hadn’t sold. We juggled about $2000 worth of baby gear over this experiment.

Parents totally rejected our initial attempt at this and we learned the importance of curating items for them: showing them fewer items curated by a trusted party.

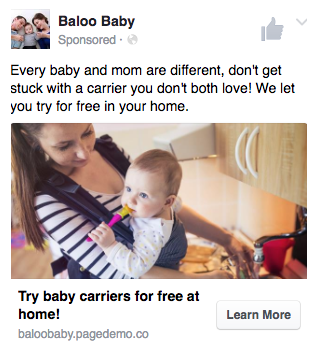

We recruited users through email, local parent lists and organizations and used facebook ads and landing pages to test conversion for different offerings.

Landing page: we were testing under the name “Baloo Baby” until we realized there is a medical condition called “blue baby”!

Parents responded very favorably to our messaging and in-home trials, and 5 out of 7 families purchased items.

Durability during tryouts wasn’t an issue, and families were surprisingly careful about not mussing up gear and reporting if any spit up or other messes had occurred.

insights from gear tasting prototype

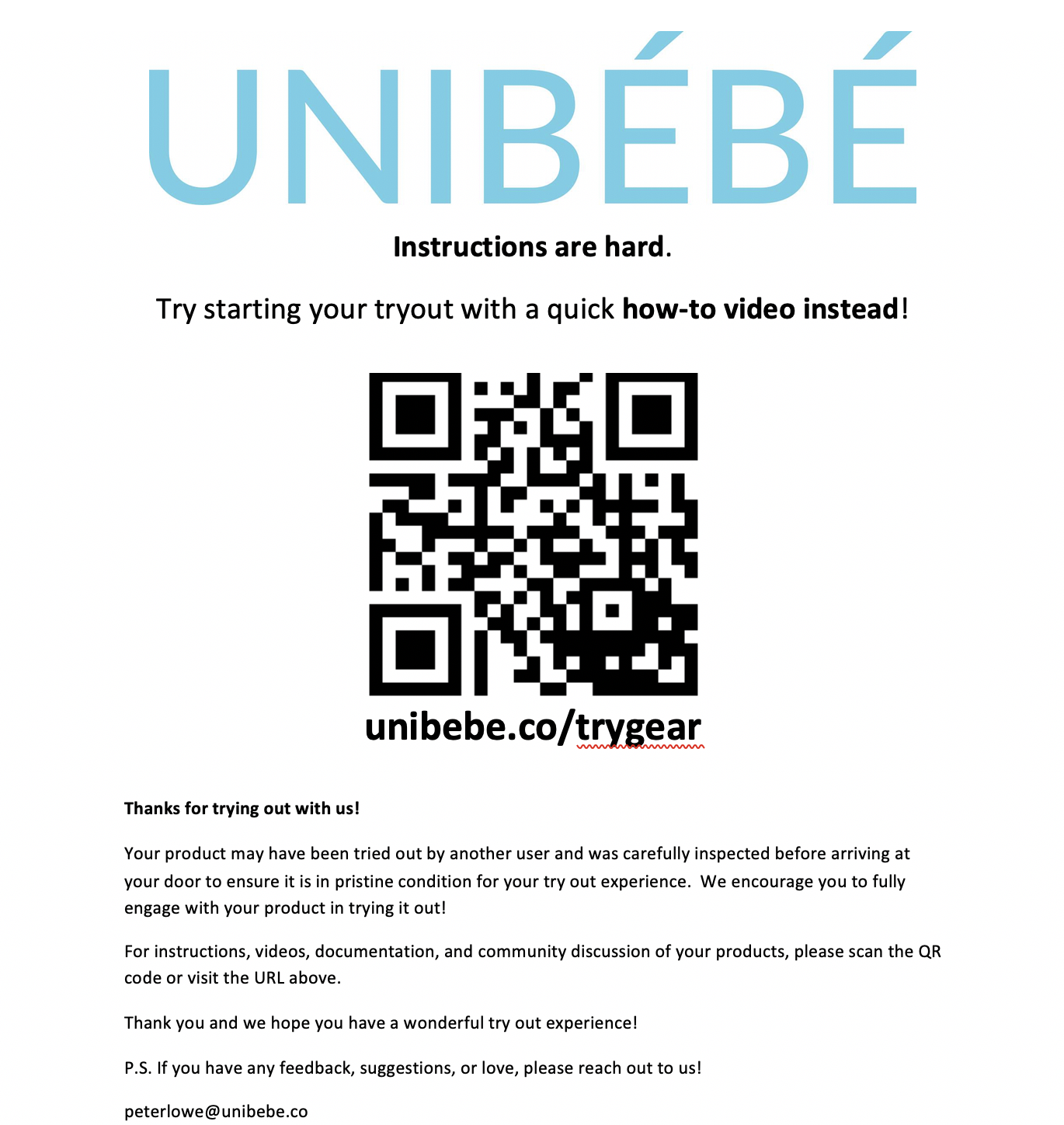

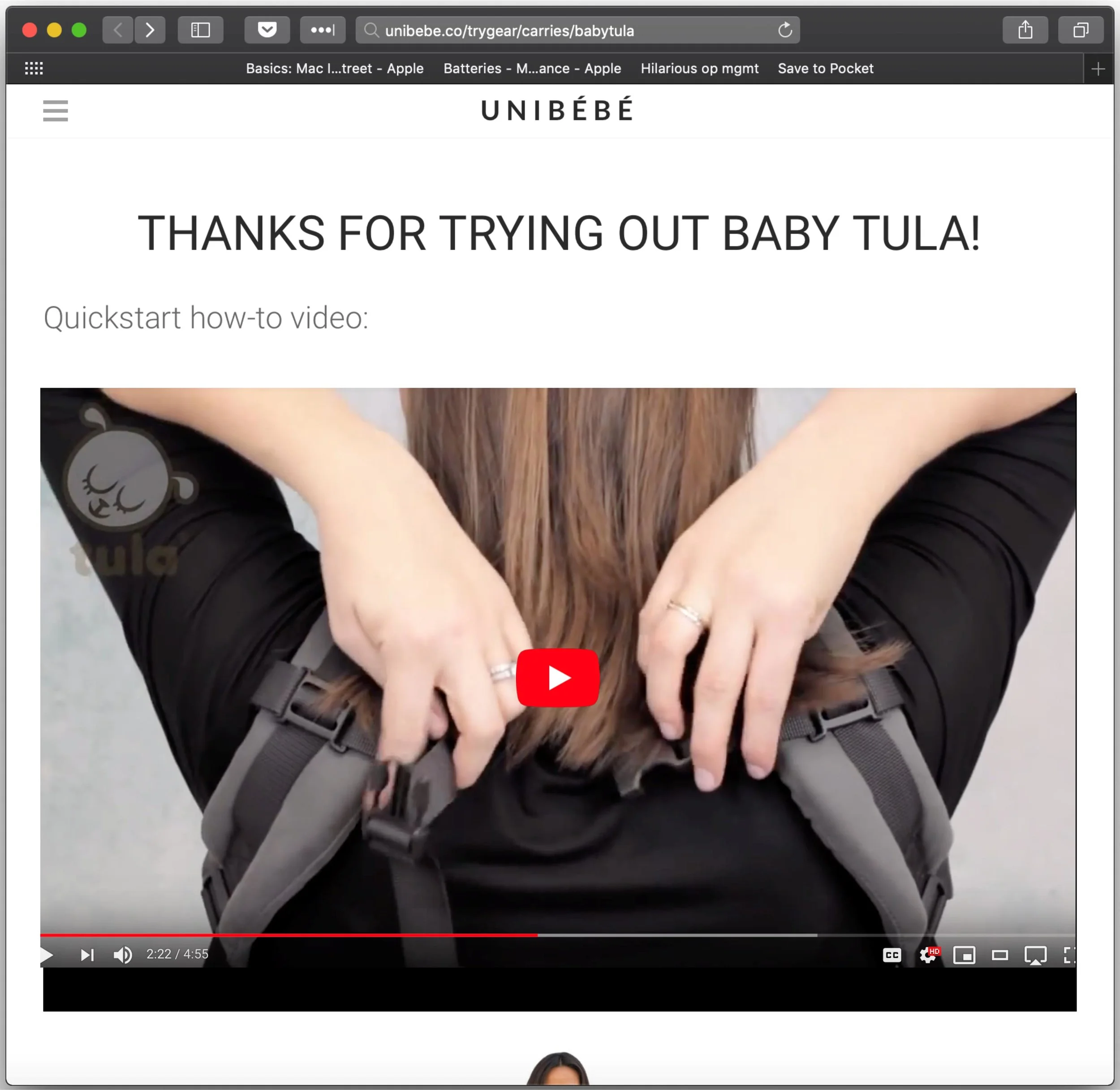

Manufacturer documentation isn’t intended for tryouts: Our in-home tryout tests revealed that instructions for baby gear aren’t very effective for getting users up to speed quickly, and parents often had to take a break before completing the tryout. We realized that new parents often become exhausted from the sheer amount of products they have to familiarize themselves with, which they have little to no prior experience with. To alleviate this, we included a page in the box to streamline the tryout process. This allowed parents to skip small confusing manuals for their initial tryout and jump directly to succinct videos. This substantially decreased tryout time, and our users felt that this “expert” guidance through the experience made the overall process of assimilating new gear considerably less stressful.

Mindsets are changing about ownership: “I’d rather store it in Amazon”

Parents mindsets are changing about owning stuff, from simply avoiding engaging with certain products in order to save themselves the hassle of getting and disposing of something, to getting rid of something with the idea that it’s stored in Amazon- they can re-buy it anytime. Attending grassroots groups like “Babywearing International” (which promotes use of slings and carriers and maintains a lending library of gear) made us realize how willing parents were to use loaned gear from trusted 3rd parties, even when it hadn’t been cleaned: they trust the organizers' judgement.

Young families are “transitional” users:

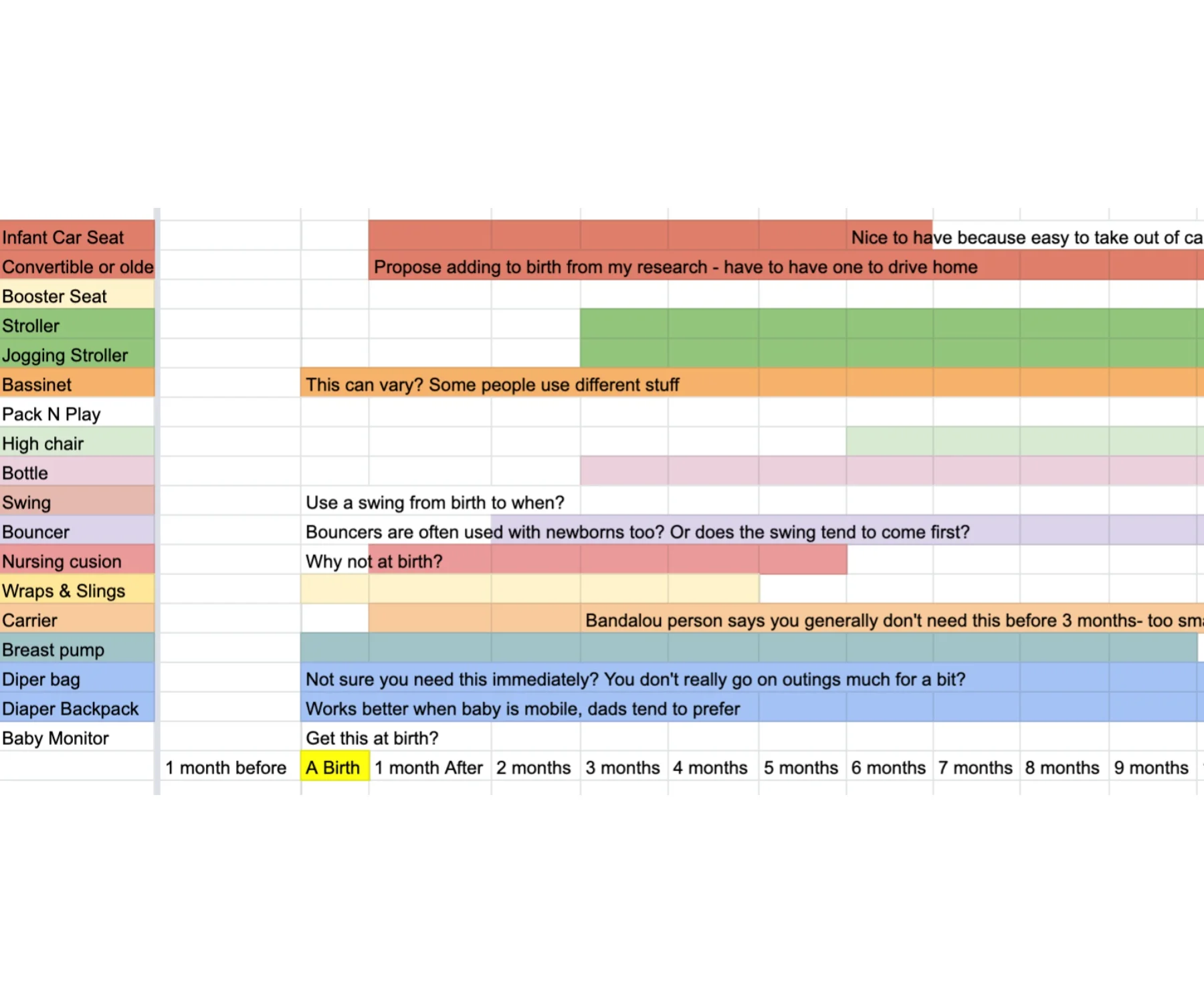

Many products have a short window of relevance, like training wheels. The short use period constrains many parents to either purchase inexpensive or used products which don’t optimally cater to their needs, break the bank on a few great products, or try to avoid these products altogether. A shared access model could enable families to have the ideal products for each moment of development, like golden training wheels.

New retailer moratorium: “Sorry, no new accounts”

Getting manufacturers to do business with non brick and mortar retailers can be tough. Brands often start in boutiques and feel beholden to them, and because industry shifts (Amazon, Buy Buy Baby) are squeezing boutiques, they pressure manufacturers not to accept new online customers. While attending the Juvenile Products Manufacturers Association show in Los Angeles, we discovered that one of the most lusted-after brands of stroller has a moratorium on new customers due to pressure from boutiques.

Concept: UNIbébé Gear Subscription

Over the course of this prototype, we continued to incorporate new feedback and evolve the concept toward an even more transformational approach which would serve our users better: never owning the gear. Although we greatly simplified the process of trying out and returning multiple products during the “gear tasting” prototype, we found that this still added difficulty, and felt that an even better solution would be to simply receive one item with frictionless trade out at any time. Although shipping the products is a significant cost now, we assume this will fall as automated shipping methods become available (Google’s Astro Teller believes cheap drone-enabled shipping will precipitate “the end of ownership”).

Another interesting result of our lenient try-out period was that new parents were sometimes happy to return gear without buying because their need for it was waning as their baby grew, and the few weeks of trying out had helped them get through the worst of a given period. Thus, it makes sense to allow families that don’t return a piece of gear to default into a competitively priced gear subscription plan without having to actually invest in every piece of gear they use. This would also allow a business model with even lower environmental impact, assuming products held up to multiple families, and eventually pave the way for an exclusive line of products designed specially for this sharing system.

Although we had a good idea of the pitfalls around shipping and tryout process by this point, the longer term subscription model presented tougher issues around sanitizing and durability.

Sanitizing: New parents’ contamination fear indicated that sanitization was an important aspect of maintaining trust in a product subscription system. Although the vast majority of pathogens that affect children die in under 24 hours away from the body and thus would be resolved simply by a day of turnaround time between families, there are a couple of exceptions such as MRSA bacteria.

With the exception of moist fabrics, most pathogens also survive much less time on soft surfaces than hard surfaces, which means that product turnaround time combined with washing any soiled fabrics and a simple antiseptic wipe over hard surfaces would resolve almost all possible issues. A more industrial-scale cleaning operation for added peace of mind could also be feasible (steam cleaning, UV or gamma sterilization, etc.).

Durability: The project timeline didn’t allow time for comprehensive durability testing of our total gear lineup, but our "gear tasting" tryouts yielded some insights. The higher end gear and electronics generally still looked new after weeks of use, with minimal cleaning needed. Experts at organizations that maintain textile gear libraries (such as Babywearing International) recommended minimizing high temperature machine wash and dry cycles to keep textiles like baby carriers from fading. We believe that instructing parents to primarily spot clean items and return them dirty for in-house cleaning could effectively address this, as well as occasional replacement of removable covers and padding.

Interestingly, the Amazon Wardrobe clothing subscription service launched within a month of the project wrapping up, and subsequent proliferation of other "sharing economy” startups like bike and electric scooter sharing startups startups suggest ongoing promise for this space.

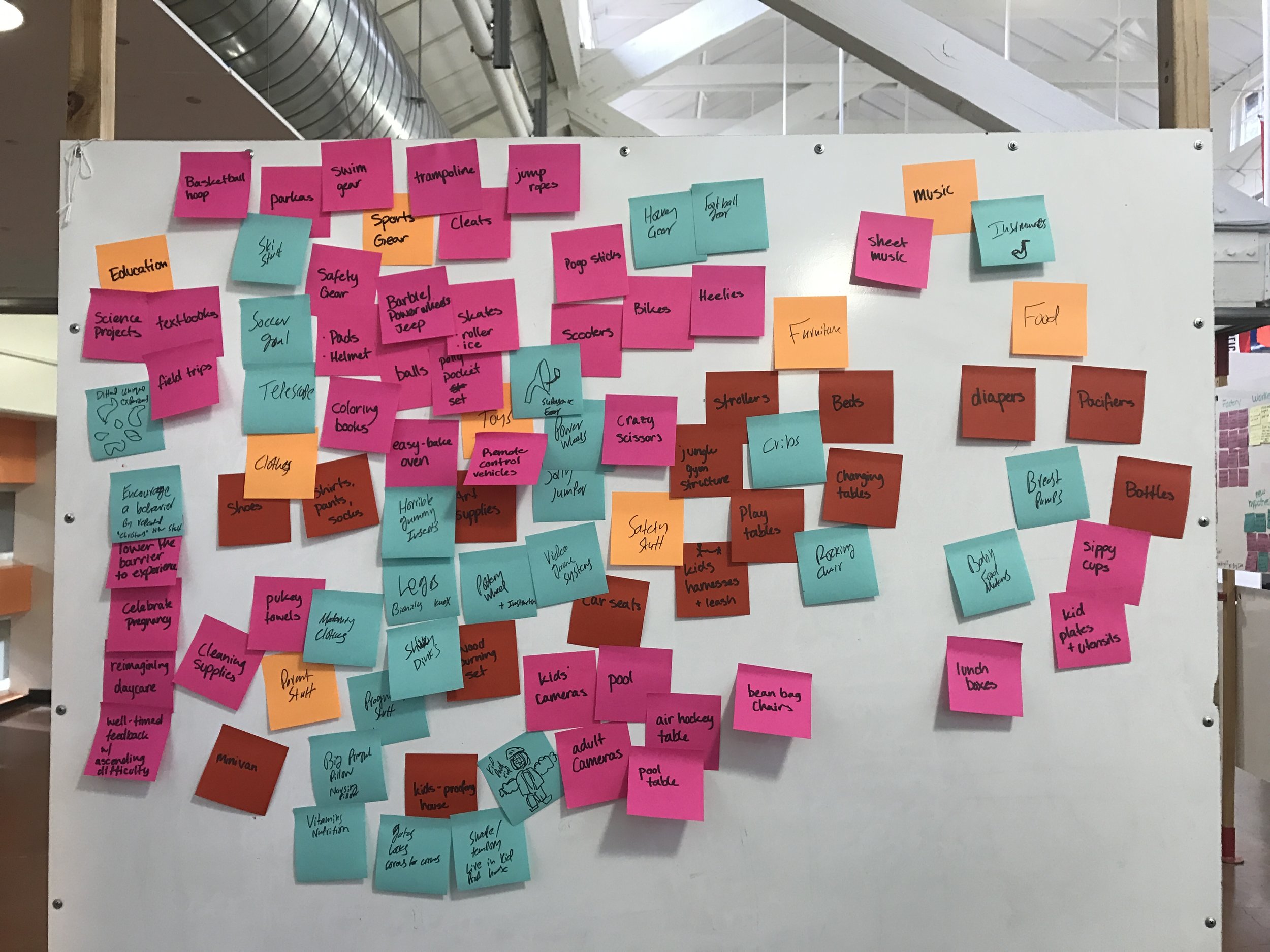

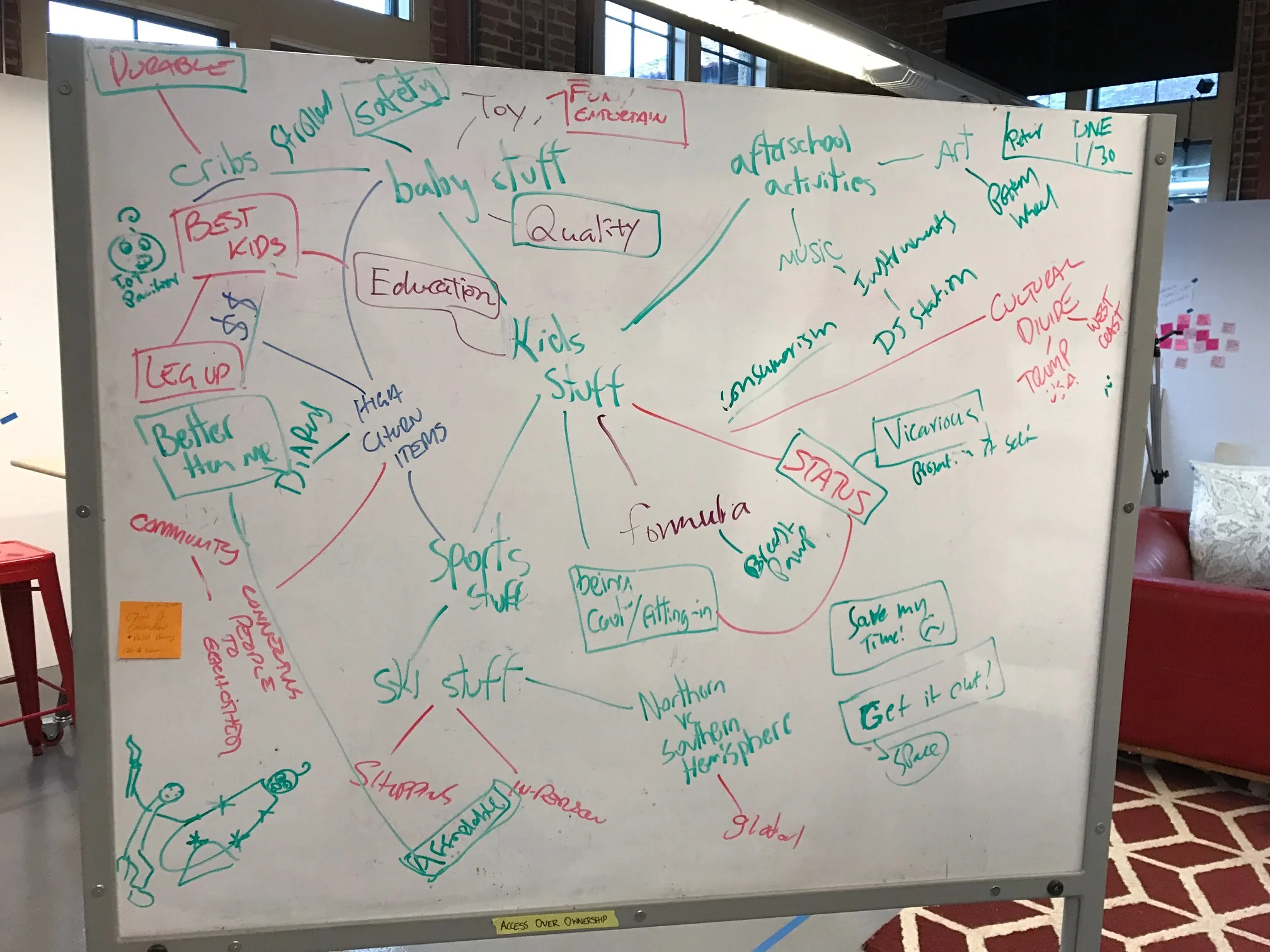

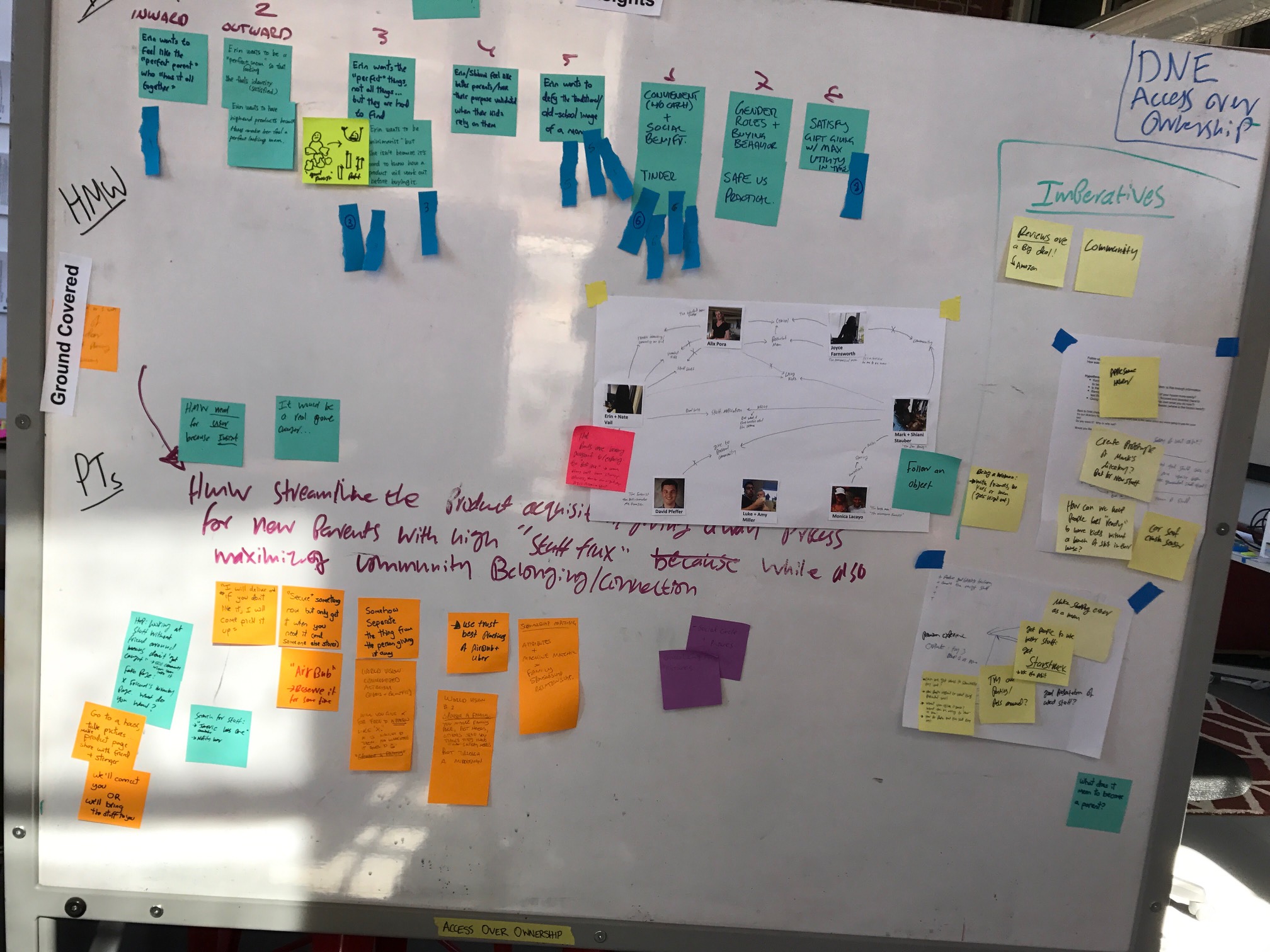

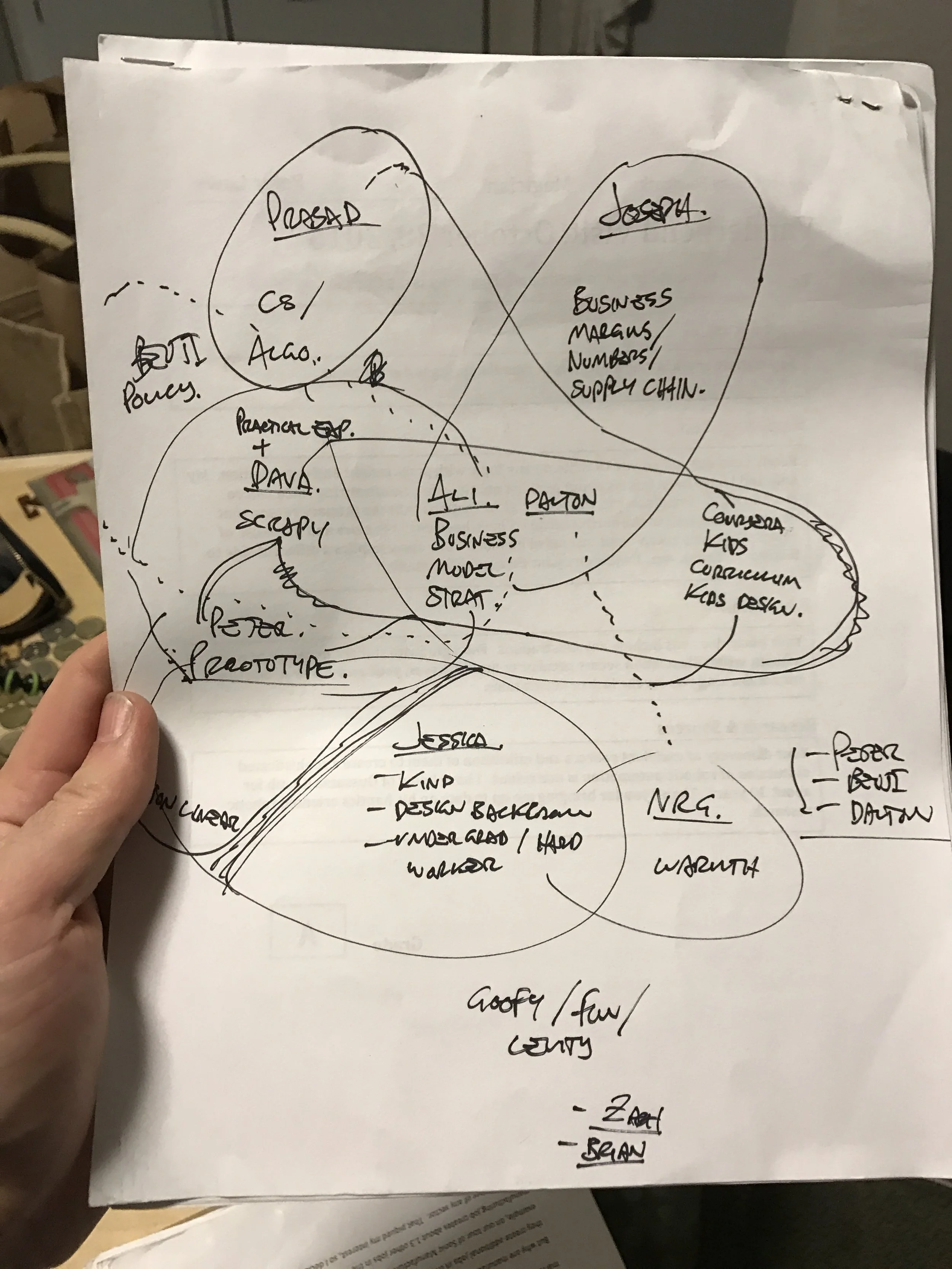

Additional images of the design process:

Footnote: Professionals today on average wait until their 30’s for marriage and/or children, and have less energy and more financial security at birth of first child as well as smaller numbers of children than previous generations (The percent of 1-child US households has doubled in the past 10 years to 23%, and this number is higher in metropolitan areas; 30% in NYC). Today’s professionals have also often moved to metropolitan areas by the time they become parents and don’t have trusted family networks close by to access secondhand baby gear. (Also interestingly, the birth rate for twins rose 76% since 1980, mostly due to aging mothers use of fertility medicines)

There are also more products and technologies available for parents than ever before which is potentially wonderful but usually bewildering for a new parent, as parents must navigate this to buy dozens of unique products for the first time, each of which often has a relevance to them of mere weeks or months.